President Franklin Roosevelt’s 982 “Guests”

Feature photo: Safe Haven Holocaust Refugee Shelter Museum, Oswego, New York

By Karen Rodriguez

“This is a true story. Few people are aware, and those who knew have largely forgotten, that nearly one thousand refugees were brought to the United States as guests of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt during World War II. Transported on an Army Transport Ship with wounded soldiers from Anzio and Cassino, hunted at sea by Nazi planes and U-boats, brought to haven in Oswego, New York, they were to know the exquisite relief of freedom from bombings and terror. Refugees from eighteen countries Hitler had overrun, they tried to rebuild their lives inside an internment camp on American soil.” (Introduction to Haven by Ruth Gruber)

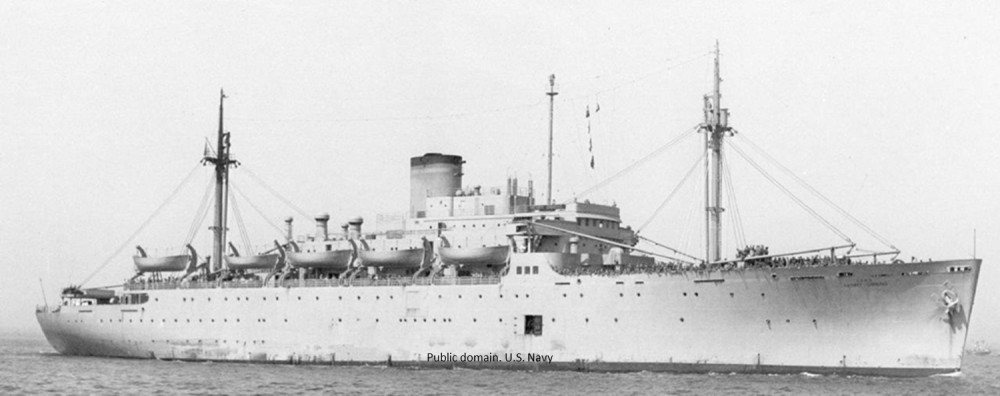

From July 21 to August 3, 1944, Ruth Gruber, special assistant to Interior Secretary Ickes, accompanied 982 refugees from the Bay of Napoli, Naples, Italy to New York, New York aboard the USAT Henry T. Gibbons. The United States Army transport vessel also held 698 wounded soldiers and 132 Army officers, civilians, Red Cross workers and American field service workers. More than a dozen military vessels protected the Gibbons from Nazi U-boats and aircraft as it progressed through the Mediterranean. After arriving in New York the refugees were transported by train to Fort Ontario, a United States Emergency Refugee Shelter located on the shore of Lake Ontario in Oswego, New York.

Gruber’s description in her book Haven of the Mediterranean/Atlantic crossing is riveting. She records Nazi attacks on the convoy as well as personal stories of the refugees as she attempts to prepare them for life in Fort Ontario. As part of the Department of the Interior’s War Relocation Authority, Gruber assisted the refugees at the camp until they were able to apply for immigration status in early 1946.

The rescue began on June 12, 1944. President Franklin Roosevelt sent a memo to the Secretaries of War, Navy, Interior, Director of the Budget, and Executive Director of the War Refugee Board outlining their joint responsibilities to select, transport, and administer a shelter for 1,000 refugees from Italy. “I have decided,” President Roosevelt announced, “that approximately 1,000 refugees should be immediately brought from Italy to this country (Gruber, Kindle location 45).” The refugees could remain “under appropriate security restrictions” for the duration of the war and after the war they would have to return to their homelands (Marks, p. 10).

Roosevelt’s directive was outside of regular immigration procedures. The War Refugee Board (WRB) was to be responsible for the entire project but its main job was to rescue people from the Nazis in Europe. Supply lines in Italy were under siege and the battles in Anzio and Cassino had further complicated those rescues. And at home, after Nazi atrocities were reported, citizens were beginning to question why the U.S. wasn’t allowing refugees into the country. The Department of Justice (DOJ) refused to allow any violation of immigration laws, thereby blocking refugees from being admitted. Government officials would have preferred that refugee camps be built elsewhere such as North Africa, closer to Europe. But that presented its own set of problems including the urgency the situation demanded. So Roosevelt circumvented DOJ and Congress and wrote the memo.

The WRB did not have a program in the U.S., so the War Relocation Authority (WRA) was tasked with managing the refugee shelter. The WRA was established under the Office for Emergency Management by Executive Order 9102 on March 18, 1942 to manage Japanese internment camps. (Executive Order 9066 ordered the evacuation of Japanese U.S. citizens from coastal areas to the interior of the U.S.) Responsibility for WRA was transferred to the Department of Interior in 1944.

More than 3,000 people applied to be one of Roosevelt’s guests. 982 were chosen based on whether they were part of a family group, a community group, or a group that had worked together; greatest need; and a cross section of skills that would be needed to maintain the shelter. No families with healthy males of military age or with contagious or loathsome diseases were accepted. Family groups were not to be separated. As many people as possible from concentration camps were accepted. Each person had to sign a statement that included the following: “I shall be brought to a reception center in Fort Ontario in the State of New York, where I shall remain as a guest of the United States until the end of the war. Then I must return to my homeland (Marks, p. 21).”

A total of 982 people representing 18 nationalities (Yugoslavs the largest group) were chosen including 874 Jews, 72 Roman Catholics, 28 Greek Orthodox, and 7 Protestants. They spoke 21 languages. 100 had been confined to Dachau or Buchenwald.

Fort Ontario, a military post since the mid-1700s, had been a special training post for the African-American 369th Infantry and the 1210th and 1212th Second Corps Service Units at the beginning of WWII. By early 1944 the camp was vacant. The barracks were prepared for the refugees.

“As they came into the fort in the early morning of August 5, 1944, the refugees presented a sorry spectacle. Their years of privation were accentuated by the discomfort of the sea voyage and the overnight ride to the shelter. Many looked haggard, unshaven, and generally unkempt. A few wore conventional summer attire, but in many cases their clothing was frayed and soiled. The most noticeable lack was that of shoes (Marks, p. 33).”

Department of Interior Secretary Ickes’ message to the refugees on the day they arrived: “I hope this haven from the intolerance, suffering, and persecution that you have undergone will in some measure ease your tragic memories (Gruber, Kindle location: 2254).” Shelter Director Smart said: “Whenever there is a knock on your door it will be a friendly one (Marks, p. 35).”

The refugees were quarantined for a month behind the barbed wire, fenced-in fort. Customs inspectors examined what passed for luggage. Second Service Command military personnel screened and fingerprinted refugees. Visitors were not allowed into the camp and refugees were not allowed to leave during the quarantine period. Incoming and outgoing mail was censored for two months. Eventually, passes were given out and refugees were given more freedom to leave the camp.

Immediately upon arrival, Oswego townspeople interacted with the refugees through the fence. After the quarantine, teen boys sneaked out to meet town girls. Children brought candy and chocolate and passed it through the fence to refugee children. By fall, children were able to attend Oswego schools. Spurred by rumors that refugees were living a luxurious lifestyle at the expense of US taxpayers, an open house brought the town into the camp to see for themselves camp conditions and to talk to the refugees. Oswego, a small community, was welcoming and compassionate.

With the help of numerous private agencies working with the WRA, refugee life in Fort Ontario attained a normalcy absent for many years in war torn Europe. But one thing was missing:

“Night. I am lying in bed, and outside the storm is howling—no, it isn’t howling; it’s racing—at forty-three miles an hour. It pipes in a hellish concert through all the seams in my lightly built quarters. I thank the Lord for the noble American nation and its wonderful President. Yes, I thank them with all my being—but. It is a “but” even after I am offered humanity, radio, underwear, clothes, shoes, food, quarters for living and recreation, and so forth. Despite all this, “but”? Yes, but. Because none offers me that for which my heart is languishing and to the sanctuary of which every last creature on God’s earth is entitled: freedom (Gruber p. 233, Kindle location: 3188-3194)!”

The war continued. The refugees learned English and adapted somewhat to American customs, and as the fate of relatives and home towns in Europe was slowly revealed, refugees became concerned about their future once the war ended. Most didn’t want to go back.

And then, in April 1945, President Roosevelt died. The refugees were in limbo. The Department of Justice maintained that the refugees were not covered by U.S. immigration laws and therefore their status was questionable (the citizenship of a baby born in September of 1944 was not settled until early 1946). In June the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization held hearings at the shelter to attempt to lay out a plan for the refugees’future. Attorney General Biddle recommended compliance with immigration laws but stated that visas or waivers could be issued by the Secretary of State.

“On Friday, July 6, 1945, the House immigration and Naturalization Committee voted that not Congress but the Departments of State and Justice ‘should ascertain the practicability of returning the refugees to their homelands.’ If that were found to be not practicable, the Attorney General should declare them ‘illegally present in the country’ and ‘undertake deportation proceedings (Gruber, Kindle location: 3680).’”

By August, 69 Yugoslav refugees had left the shelter for Yugoslavia, South Africa, Uruguay and Czechoslovakia. Representatives from the State, Justice and Interior Departments interviewed the remaining refugees to determine where they wished to live and whether it was feasible to accommodate their wishes.

President Truman sent Earl G. Harrison, Dean of Law at the University of Pennsylvania and representative on the Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees, to Germany to investigate existing displaced persons camps. How feasible was it to return the refugees to post-war Europe? In his report to the President, Harrison stated: “We appear to be treating Jews as the Nazis treated them except we do not exterminate them (Gruber, Kindle location: 3754).” Harrison said repatriation would be inhumane. He recommended resettlement.

On December 22, 1945, shocked by Harrison’s report of the horrible conditions in Europe, Truman made a decision: “I am therefore directing the Secretary of State and the Attorney General to adjust the immigration status of those members of this group who may wish to stay here, in strict accordance with existing laws and regulations (Gruber, p. 277, Kindle location: 3891-3892).”

“To enter the United States legally, they had to leave it. On January 17, 1946, the first three busloads, carrying ninety-five refugees, left camp at six in the morning. They drove across western New York State to Buffalo, where the community invited them to a roast-beef lunch in Temple Beth El. Then the buses traveled to Niagara Falls and crossed the Rainbow Bridge to the town of Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada. There they were greeted by George Graves, the American consul, who gave each refugee the longed-for visa embellished with a red seal and a ribbon. They drove back across the Rainbow Bridge and at last entered America (Gruber, p. 279, Kindle location: 3930-3938).”

Ruth Gruber documented what happened to refugees after crossing the Rainbow Bridge back into the United States and eventually obtaining citizenship. Refugee Alec Margulis became the chief of radiology at the University of California. He developed the CAT scan and the MRI. Rolf Manfred was one of the creators of the Polaris and Minuteman missiles. Joseph Langnas and Neva Gould, among others, were physicians. Ivo John Lederer became an author, teacher and historian. Irving Schild was a photographer and chairman of the photography department at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology. Jetta Hendel became the United Nations representative of the nongovernmental Pan Pacific and Southeast Asia Women’s Association. Harry Mauer worked for NASA and the Air Force. Among the new citizens were hairdressers, doctors and nurses, professors/teachers, retail salespeople, artists—photographers/painters/poets/actors, engineers, computer specialists, social workers, secretaries, foremen, flight attendants, and lawyers.

“They had helped give back to America the kind of human values that made it great. Whether it was genes, heritage, an inborn passion for learning, or their strength as survivors, they absorbed with relish and enthusiasm what America offered and, in turn, made their own unique contributions. How grateful my country can be for having given them haven (Gruber, p. 297, Kindle location: 4181-4184).”

The books:

Gruber, Ruth. Haven, the Dramatic Story of 1,000 World War II Refugees and How They Came to America. New York, NY: Open Road Integrated Media. 2010. www.openroadmedia.com. Originally published in 1983.

Marks, Edward B. Token Shipment, The Story of America’s War Refugee Shelter, Fort Ontario, Oswego, New York. United States Department of the Interior, War Relocation Authority. 1946. Revised and illustrated in 2017.

Websites for Safe Haven Museum and Fort Ontario:

https://parks.ny.gov/historic-sites/20/details.aspx

Content copyright 2018 Karen Rodriguez

Thank you for presenting this article. We certainly need good work to be reported in these times. This country is made up of immigrants and is richer for it. Also, how precious freedom is. Please protect it!

LikeLiked by 1 person