Her Fight for Emancipation and Dignity

Feature photo: Harriet Tubman. Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, National American Woman Suffrage Association Collection. JK1881 .N357 sec. XVI, no. 3-9 NAWSA Coll series: Miller NAWSA Suffrage Scrapbooks, 1897-1911; Scrapbook 9 (1910-1911); http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.rbc/rbcmil.scrp7004801

By Karen Rodriguez

“I would make a home for them in the North, and the Lord helping me, I would bring them all here.” Harriet Tubman

In 1892 Harriet Tubman was granted an $8.00 per month widow’s pension in compensation for her Civil War service as a nurse, cook and a spy for the US Government’s Department of the South. At last, with a guaranteed pension and a bank loan secured with the help of the AME Zion Church, she was able to purchase 25 acres next to her Auburn, New York home and open a charity home for needy black Auburn residents.

Tubman had settled in Auburn in 1857. By this time her role as a conductor in the Underground Railroad was known. One prominent resident who had married into an Auburn family, Senator William Seward**, recognized Tubman’s bravery. He sold Tubman a home she could afford as a reward for her work. This home was often used as her Underground Railroad base of operations over the next couple of years.

Of her early life little is known. Because slaves were considered property and most were illiterate, few records of life events were kept with the exception of the slave auctions. It is known that Tubman was born sometime between 1815 and 1825 (her gravestone says 1820) as Araminta Ross to slaves Harriet Green and Benjamin Ross on the Brodess plantation, somewhere near Bucktown, Maryland. She may have had a dozen siblings but it is unclear how many. Her grandmother, Modesty, had arrived on a slave ship and was bought by an Eastern Shore (Maryland) family named Pattison. Her heritage may have been African Ashanti. But no one, including Tubman, knew for sure.

As a girl as young as perhaps five years old, Araminta was sold to various families as a housekeeper, child care worker and whatever else was demanded of her. Overworked, often starved and beaten, by the time she was 12 years old she began working in the fields. When about the age of 13, she blocked an overseer from pursuing a field hand he intended to whip for some infraction. The overseer picked up a lead weight and threw it at the field hand but missed, instead hitting her in the head. Ill for months, the injury plagued her for the rest of her life. The injury is thought to have manifested itself as narcolepsy and hypnagogic hallucinations.

In 1844 slave Araminta Ross and free black John Tubman entered into an informal arrangement. Their arrangement was controlled by the slave owner; slaves and free blacks were not allowed to marry. Nothing is known about John Tubman’s background or his trade as a free man.

In 1849 Araminta’s master died and plantation rumor said she would be sold along with a couple of her brothers. She fled, alone, to Philadelphia where she found work and a welcoming group of both former slaves and abolitionists. Soon after, she changed her name from Araminta Ross to Harriet Tubman.

Several events greatly influenced the abolitionist movement mid-century. On Sept. 18, 1850, the Fugitive Slave Law was approved by the U.S. Congress. The Law was a part of the Compromise of 1850, drafted to attempt to settle differences regarding slavery between the northern and southern states. Named the “Bloodhound Law”, it allowed escaped slaves to be remanded to their “owners” from any state. Slave owners’ “property” rights were thereby protected; monetary rewards for capturing slaves encouraged vigilante actions. Activists such as Thomas Garrett, abolition leaders like William Lloyd Garrison and former fugitive Frederick Douglass spoke openly and widely against the law. The law was immediately deemed unconstitutional by cities like Chicago, which nullified the law within the city limits. One result was that within three months 3,000 ex-slaves fled to Canada.

A million copies of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in March of 1852, were sold in its first year of publication. The book helped to open peoples’ eyes to the evils of slavery. Although Tubman could not read, she no doubt knew of the book’s popularity and the resulting shift in awareness regarding slavery.

“If you are tired, keep going; if you are scared, keep going; if you are hungry, keep going; if you want to taste freedom, keep going.” (Harriet Tubman’s refrain during her Underground Railroad years. Clinton p.221)

In the winter of 1851-1852 Tubman returned to Maryland to free her niece Kizzy and Kizzy’s two children. She returned a second time in the spring to rescue one of her brothers and several other men. Her third trip in late 1851 was to rescue John Tubman. But he had another woman by that time and refused to leave. Instead, she rescued 11 others including another brother. For the first time she took them across the border to St. Catharines, Ontario.

In 1793, under leadership of John Graves Simcoe, Lieutenant Governor of the British colony of Upper Canada, the Executive Council of Upper Canada had passed the Act to Prevent the further Introduction of Slaves and to limit the Term of Contracts for Servitude within this Province. The law protected current slaveholders, stated that children born to slaves would be free at age 25, and prevented the importing of new slaves. Numerous settlements in Canada for blacks escaping the U.S. arose as a result. St. Catharines became Tubman’s home for her and her freed family for many years.

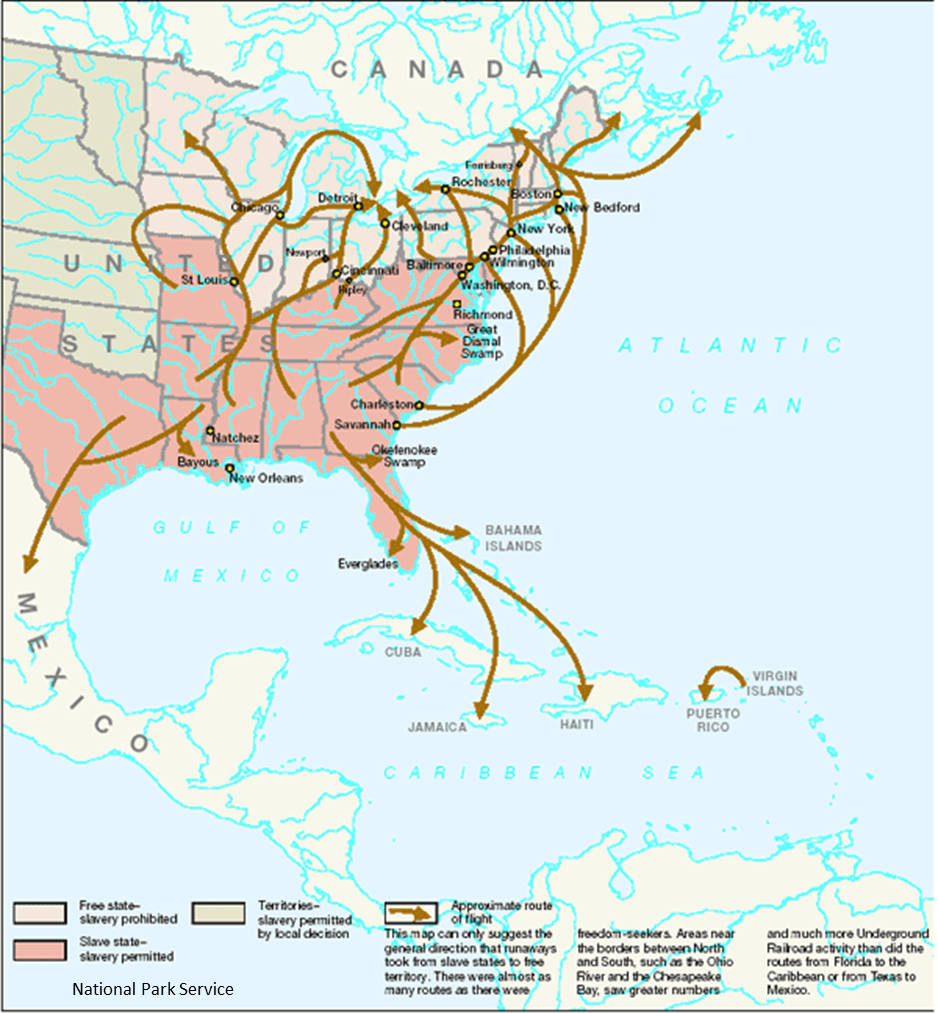

Underground Railroad conductors did not keep a record of their raids or the people they brought to freedom partly because many, like Tubman, were illiterate, and partly because secrecy was paramount to protecting both conductors and fugitives. Between 1854 and 1856 alone it is estimated Tubman raided plantations in Maryland and Virginia to free between 70-200 slaves.

Fearless, Tubman traveled at night. She knew the landscape and the safe houses from Maryland and Virginia to Philadelphia, New York and St. Catharines. She had a sixth sense for danger and a religious faith that seemed to protect her and those she freed. She hid fugitives in marshes and woods, forded rivers, and avoided gun toting vigilantes. Not a single person in her care was lost.

“She would return again and again to the South, cheered on by former fugitives, but never joined by them on her expeditions. She alone took these risks, eventually bringing hundreds out along liberty lines to freedom. Even with a concealed identity and clandestine partnerships, her above-ground fame grew. With her spectacular achievements, she was likened to the biblical hero of her code name, Moses.” (She was named Moses by abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. Clinton p. 85)

Tubman spent the first year of the Civil War as a nurse and cook for African American soldiers and civilians in Beaufort, South Carolina. In 1863 General Saxton, under the direction of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, asked that Tubman work with Major General David Hunter to recruit scouts to map the interior of southern states held by the Confederates.

Espionage by Tubman and her scouts led to the Combahee River raid of June 1863. In the middle of the night Tubman, Colonel James Montgomery***, and 150 black soldiers on board Union gunboats, sailed up the river past torpedoes she had mapped to the South Carolina rice plantations near the Atlantic Ocean shoreline. The estates of elite land and slave owners were raided and set on fire and more than 700 slaves, many with their livestock, escaped to the gunboats and to freedom. All escaped unharmed.

Tubman’s health deteriorated after the Civil War. Nevertheless she continued to give speeches and to care for the poor in Auburn well into the early 20th century. Throughout the remainder of her life, the citizens of Auburn embraced Tubman as a former leader in the Underground Railroad, a Civil War heroine, and a civil rights activist who delivered mesmerizing speeches throughout the country. By the time of her death in Auburn on March 10, 1913 (Rosa Parks’ birth year), Tubman was an international figure:

“A lifelong humanitarian and civil rights activist, she formed friendships with abolitionists, politicians, writers and intellectuals. She knew Frederick Douglass and was close to John Brown and William Henry Seward. She was particularly close with suffragists Lucretia Coffin Mott, Martha Coffin Wright, and Susan B. Anthony. Intellectuals in New England’s progressive circles, such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, William Lloyd Garrison, Bronson Alcott, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Franklin B. Sanborn, and Mrs. Horace Mann, befriended her, and her work was heralded beyond the United States.” (National Park Service)

*Harriet Tubman National Historic Park, Auburn, New York; https://www.nps.gov/hart/index.htm

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park https://www.nps.gov/hatu/index.htm.

**William Seward: Governor of NY 1939-1842; US Senator from NY 1849-1861; President Lincoln’s Secretary of State during the Civil War 1861-1869

***Colonel James Montgomery: a trusted lieutenant of John Brown during the Kansas border wars. Tubman and Montgomery knew each other

The books:

Bial, Raymond. The Underground Railroad. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. 1995.

Bradford, Sarah Hopkins. Harriet, the Moses of Her People. New York: Geo. R. Lockwood & Son. 1886.

Clinton, Catherine. Harriet Tubman, the Road to Freedom. New York: Back Bay Books, Little, Brown and Company. 2004.

Siebert, Wilbur H. The Underground Railroad, from Slavery to Freedom, A Comprehensive History. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications Inc. 2006.

Still, William. The Underground Railroad, a Record of Facts, Authentic Narrative, Letters, &C. First published in Philadelphia in 1872.

Stowe, Harriet Beecher. Uncle Tom’s Cabin. First published in 1852.

Washington, Margaret, Editor. Narrative of Sojourner Truth. New York: Vintage Classics. 1993 (first published in 1850).

The story and photos except for the maps and 1793 Act copyright 2019 Karen Rodriguez.